By Simon Olling Rebsdorf, climate and science advocate, PhD, Author

We know what needs to be done. We have known for decades. Climate change, biodiversity loss, resource depletion – these crises are no surprise. Scientists have warned us, the data is clear. And yet, the world keeps delaying action. Why?

It is frustrating and even bewildering that despite our knowledge, meaningful change stalls. The reasons go beyond ignorance. They are psychological, economic, political, and sociocultural barriers.

These forces shape how we think, act, and apparently justify inaction. They give us excuses that feel logical, even when they are destructive. Understanding these barriers can be empowering, but it can also reveal how difficult the challenge truly is – a double-edged sword that we must wield carefully to avoid paralysis.

Psychological barriers

Our minds struggle with long-term threats. Many of us experience cognitive dissonance, the tension between knowing what is right and doing the opposite. Facing that discomfort, we often rationalize instead of changing.

“One person can’t make a difference.”

“Technology will fix it.”

We tell ourselves comforting stories to reduce the guilt. These rationalizations become mental excuses that allow us to continue with business as usual, even if we intellectually know better.

We also suffer from short-term bias – the future feels distant and abstract, while immediate rewards (or avoiding immediate costs) feel more pressing. Preventing a disaster decades from now doesn’t motivate us as strongly as tangible benefits today. And then there is optimism bias – the belief that bad things happen to others, not us. We assume we’ll somehow be spared or that incremental efforts will suffice. This bias feeds a false sense of security, making the climate crisis seem less urgent on a personal level than it truly is.

Economic barriers

The market does not reward long-term thinking, which creates structural excuses for inaction. Externalities – like pollution and deforestation – are hidden from the prices of goods and services. Those who profit from harmful activities are rarely the ones who pay for the damage. A classic example is the tragedy of the commons, where shared resources (fish stocks, forests, the atmosphere) are overexploited because everyone waits for someone else to act first. In a profit-driven market, doing the right thing often puts a company at a short-term disadvantage, so the destructive status quo persists.

There is also an obsession with short-term profit in our economic system. Companies prioritize quarterly earnings and rapid growth over sustainability. Governments fear the political fallout of economic slowdown more than the slow-burn catastrophe of climate change. Investments in clean energy or conservation, which may only pay off years down the road, are frequently shelved in favor of projects that promise quick returns. This short-termism in economics provides a convenient excuse:

“We can’t afford to sacrifice growth now for uncertain benefits later.”

In reality, this mindset simply pushes off the costs to future generations.

Powerful industries actively lobby against change that would threaten their interests. Fossil fuel companies, in particular, have spent enormous sums (over decades) to influence policy and public opinion. Just as tobacco giants once obfuscated the dangers of smoking, oil and coal interests have funded disinformation campaigns to sow doubt about climate science and delay action.

This policy capture means laws often favor business-as-usual over long-term planetary health. The influence is subtle but pervasive: regulations get watered down, renewable energy incentives stall, and leaders may downplay environmental crises under pressure from these lobbies.

Political barriers

Meanwhile, political short-termism means elected officials focus on the next election, not the next century. Policies that demand sacrifice today but bring benefits in 50 years are notoriously hard to sell. It’s easier for politicians to punt tough decisions to their successors than risk voter backlash now. Add to that ideological polarization – global challenges become fodder for culture wars instead of areas for cooperation. In some circles, even acknowledging scientific facts becomes a political litmus test. As a result, science itself gets questioned or ignored if it doesn’t fit a convenient narrative. All of this creates a system with high inertia: even well-intentioned leaders find it difficult to enact bold climate policies in the face of partisan gridlock and vested interests.

Socio-cultural barriers

Change is hard when social norms stay the same. There is a powerful social inertia in our communities: we tend to mirror the behavior of those around us. If everyone else seems unconcerned and continues with high-carbon lifestyles, it feels “normal” to do the same. Going against the grain by radically changing one’s lifestyle or advocating for drastic measures can make one feel like an outlier. This herd behavior subtly excuses inaction – “No one else is panicking, so maybe it’s not that urgent.” Maintaining social conformity often wins out over sounding the alarm.

Misinformation also clouds public understanding. Decades of deliberate climate denial campaigns have left a residue of confusion and false debate. Even today, many people underestimate the scientific consensus on climate change or believe outright myths (like “climate change is a hoax”). This engineered doubt gives cover for inaction: if the problems are not fully certain, why commit to expensive solutions? And then, at the opposite extreme, there is doomism – the belief that it’s too late or nothing can be done, so why bother trying? Ironically, giving up hope can feed inaction just as much as outright denial. If one believes humanity is inevitably doomed, any effort seems pointless, and apathy becomes justified. Both denial and doomism serve as psychological escape hatches, avoiding the difficult work of change.

Worldviews and their influence on action

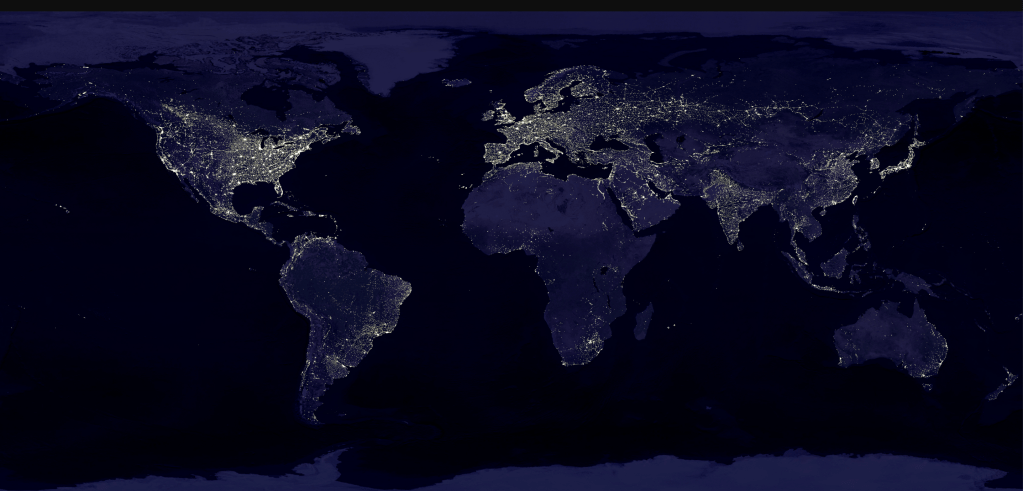

The brightest areas on the above satellite image are the most urbanized – a vivid display of how humanity has become a global force shaping the planet. How we interpret and respond to this reality depends on our worldview.

Our worldview acts as a lens that filters those psychological, economic, political, and cultural barriers. It influences whether we treat these barriers as solvable challenges or unavoidable fate. In fact, understanding why we keep making excuses is inseparable from how we view humanity’s role in nature.

Eco-modernism

One dominant perspective is eco-modernism, which aligns closely with optimism bias and techno-optimism. Eco-modernists acknowledge the Anthropocene – the idea that humans have become a geological force transforming Earth – but see human ingenuity and technology as the way forward . In this view, continued progress (through innovation, nuclear energy, GMOs, geoengineering, etc.) can decouple human well-being from environmental impact.

Problems like climate change are seen as engineering challenges we will solve, not existential limits. This mindset provides a sort of built-in excuse for the status quo: if future technology will save us, dramatic socio-economic changes or sacrifices today seem less necessary. A “good Anthropocene,” eco-modernists argue, is achievable with enough investment in science and smart policy, allowing both human prosperity and an ecologically vibrant planet. The risk, however, is that this mindset can slide into complacency – assuming someone (scientists, entrepreneurs, engineers) will fix things in time, so the rest of us need not change much.

Eco-Marxism

In contrast, eco-Marxism (and related eco-socialist thought) shifts the blame for ecological crisis from humanity as a whole to the capitalist system. From this perspective, we are not just in the Anthropocene but in what some call the Capitalocene – an era shaped by the logic of capitalism and its endless pursuit of profit. It’s not human nature that drives destruction, it’s a specific economic order.

The imperative of profit maximization leads to overconsumption, pollution, and extraction without regard for limits . In this view, the optimism of ecomodernism is not just naive but a deliberate illusion that sustains the status quo. Techno-fixes promoted under capitalism are seen with suspicion – are they real solutions or just new ways to make money?

Eco-Marxists would argue that without addressing economic power structures and wealth inequality, any “green” efforts will be co-opted or insufficient. The call is for system change: a revolutionary shift away from capitalism’s growth-at-all-costs model, because only by altering the system that produced the crisis can we truly solve it. This worldview frames inaction as a result of capitalist hegemony: the people most able to act (corporations, the wealthy, governments in capitalist societies) are incented not to change. Thus, overcoming our excuses requires an overthrow of entrenched economic interests.

A new materialism

The advent of new materialism challenges both of the above perspectives. Rather than seeing “humanity” and “nature” as separate or opposing forces, new materialists emphasize the entanglement of human and non-human agencies. This holistic, post-humanist approach resists the simple narratives offered by both technological optimism and economic determinism. In other words, it’s not just about clever humans inventing fixes (as ecomodernists imply) or just about a capitalist system to be overthrown (as eco-Marxists imply) – it’s about fundamentally rethinking our relationship with the material world. New materialism posits that agency is distributed: humans are influencing the planet, yes, but the planet (and its systems) also profoundly influences humans. We exist in webs of interdependence. This perspective asks us to question the notion of human dominance or exceptionalism; it places humans on the same level as the rest of nature, neither above nor below in moral or existential status . By doing so, it urges a kind of humility and a new form of responsibility.

New materialism’s critique of our excuses is subtle but powerful. If we truly grasp that we are entangled with non-human forces, the old dichotomies (individual vs. collective action, personal sacrifice vs. tech innovation) start to dissolve. This view says: the way we’ve framed the problem might itself be part of the problem. We look for external fixes or scapegoats (“technology will save us” or “capitalism is to blame”) without recognizing that our thinking is still caught in an outdated human-versus-nature mindset. By rethinking agency and acknowledging that we co-exist with many active forces within planetary limits , new materialism calls for a deeper transformation in how we live. It’s not a simple answer or ideology, but rather a paradigm shift: we must change not only our actions, but the very concepts we use to understand those actions.

This new materialist perspective is echoed in the work of philosopher Timothy Morton, who introduces the idea of hyperobjects. A hyperobject is a phenomenon so massively distributed in time and space that it defies our usual ways of thinking. Climate change itself is often cited as a prime example – it’s everywhere and at all times, yet we can never fully see it as a whole. Morton argues that hyperobjects like global warming or plastic pollution force us to upgrade our mental toolkit. They are, as he puts it, “massively distributed in time and space relative to humans” . We can’t hold a hyperobject in our hand or see it in one snapshot; we piece it together from data, models, and disparate experiences. This has profound implications for human-nature relationships: it underlines that we are deeply entangled in systems far bigger than ourselves. We are “always inside an object,” Morton quips – meaning, for instance, we live within the climate system, not apart from it.

The concept of hyperobjects dismantles any comfortable notion that humans stand at the center of the world. In fact, hyperobjects de-center us: they show that there is no single human perspective that can oversee the whole. This realization can be disorienting, even “humiliating” for humanity’s ego, but it is ultimately enlightening. It compels us, as Morton says, to think ecologically, rather than imagining we can dominate or manage nature from the outside . In the context of our excuses, hyperobjects put a spotlight on why our normal intuition fails. We don’t directly feel climate change in the same way we feel a cold day or a hot stove – it’s too vast, too drawn out. So we struggle to act on it. Recognizing climate change as a hyperobject can help explain our paralysis: our minds aren’t well-equipped to grapple with entities of this scale. This doesn’t let us off the hook, but it suggests we need new cognitive and emotional strategies to deal with such challenges.

Mads Ejsing’s book Verden er ikke længere den samme (“The world is no longer the same”, 2024) builds on these new materialist ideas. He argues that we must rethink our relationship to the world, not just our actions within it . If we fail to do so, we risk falling into the same patterns of delay and self-justification that got us here. In practice, this might mean reinventing how we talk about progress, success, and happiness in society. Do we continue to equate a good life with ever-increasing consumption? Or can we define it in terms of balance, resilience, and respect for our ecological home? Such questions indicate that overcoming our collective inertia is not only a technical or political challenge, but a philosophical and cultural one.

Breaking the cycle: From understanding to action

All these barriers and worldviews paint a complex picture of why we keep making excuses. It can be overwhelming – almost paralyzing – to realize how many forces conspire to maintain the status quo. After all, if our own brains, our economic systems, our politics, and even deep-seated worldviews are stacked against rapid change, what hope do we have? It’s normal for a reader to feel a knot of despair or frustration at this point. Understanding the barriers can indeed frustrate us further, because it reveals the magnitude of the problem. However, that understanding can also be empowering. By naming the excuses and dissecting the barriers, we shine light on the hidden forces of inertia. What once was an amorphous sense of “why nothing changes” becomes a clearer map of challenges. And a map, no matter how disheartening, at least shows possible routes forward.

Overcoming these entrenched barriers will be undeniably difficult. The systemic inertia – in our infrastructure, institutions, and habits – means progress often feels excruciatingly slow. Yet acknowledging this difficulty is part of maintaining intellectual rigor. We shouldn’t delude ourselves that a simple tweak or silver bullet will solve everything. No, the analysis here makes one thing clear: only a multifaceted approach, attacking each excuse and barrier, stands a chance. That said, analysis must not give way to fatalism. We have to balance the clear-eyed assessment of systemic challenges with a refusal to give in to them emotionally. Yes, it is hard to change entrenched systems – but it is not impossible. History is full of social paradigms that seemed immovable until suddenly they shifted (often because dedicated people kept up the pressure for years).

Crucially, we must guard against the very paralysis we seek to diagnose. There is a risk that after examining all these obstacles, one ends up thinking: “If everything is stacked against us, perhaps we truly can’t do anything.”

But that is another excuse – a last-ditch one that combines despair with self-absolution. The truth is, understanding why we delay change is the first step to breaking the cycle . When we see excuses for what they are – mental shortcuts or comfortable myths, not insurmountable walls – we can start to challenge them. Each of us can notice when we’re rationalizing (“maybe the next generation will handle it”) and gently correct course. We can call out misinformation when we see it. We can support leaders and policies that tackle root causes, not just symptoms. We can cultivate narratives of hope and resilience to counter doomism, without slipping into naive optimism.

To act is to reject paralysis. It means deciding, even in the face of uncertainty and even with no guarantee of success, that we will do what we can. Action can take many forms: voting, protesting, educating, innovating, conserving, building community. It can be small-scale or systemic. What matters is the refusal to be inert. In the end, standing firm despite the complexity and enormity of the task is a profound expression of our humanity. It’s an assertion that we are not just passive products of our circumstances or worldviews – we also have the capacity to reflect and choose differently.

Overcoming our excuses is about reclaiming agency. It’s about saying: Yes, the deck is stacked, and yes, we are flawed – but we are not helpless. We can reinvent our economies, we can reform our politics, we can reshape our cultural stories about what it means to live well on this Earth. It won’t happen overnight, and the effort will test our patience and resolve. There will be times of intense emotional frustration as progress stalls or backlash surges. But each barrier understood is a barrier that can be weakened, circumvented, or dismantled piece by piece.

Ultimately, confronting these excuses is an ethical choice to live in truth rather than comfort. It is choosing responsibility over convenient escape. That choice, repeatedly made, can become a new norm – a new culture of accountability to the future. And that is the essence of eudaimonia (human flourishing) in an age of crisis: not a blissful ignorance, but a hard-won integrity. To stand up and act, in spite of everything, with clear eyes and a steadfast heart with dignity – that is to reject paralysis.

Further Reading

Future of Humanity Institute (FHI)

A (closed) interdisciplinary research center at Oxford University focusing on existential risks and long-term global challenges. Still the treasure trove of ressources are made available to all.

The Long Now Foundation

Promotes long-term thinking and responsibility through projects like the 10,000-Year Clock, encouraging a broader perspective on our future.

CUHRE – Elite Centre for Understanding Human Relationships with the Environment

A multidisciplinary research center at the University of Southern Denmark (SDU) that explores how humans relate to the environment and develop sustainable coexistence strategies.

Institut for Vilde Problemer

A think tank addressing complex societal issues, fostering dialogue and innovative solutions for pressing global challenges.

Visit Institut for Vilde Problemer

CONCITO – Denmark’s Green Think Tank

Focuses on analyzing and promoting green policies and sustainable solutions in Denmark.

Stockholm Resilience Centre (SRC)

An international research center dedicated to studying resilience and sustainability in social-ecological systems from a global perspective.

Visit Stockholm Resilience Centre

The New Institute

A think tank in Hamburg that integrates philosophy, art, and science to address global challenges and stimulate new narratives.

Ellen MacArthur Foundation

Focuses on promoting the circular economy by developing innovative models for sustainable business and societal practices.

Visit Ellen MacArthur Foundation

The Dark Mountain Project

A network of writers and artists exploring humanity’s place in a changing ecological landscape through storytelling and creative expression.

Visit The Dark Mountain Project

Club of Rome

Famous for its report “Limits to Growth,” this organization explores systemic solutions to global economic and environmental challenges.

The Center for Humans and Nature

Investigates human-nature relationships through philosophical and cultural lenses, emphasizing ethics and hope for a sustainable future.

Visit The Center for Humans and Nature

References for inspiration

1. Gifford, R. (2011). The Dragons of Inaction: Psychological Barriers That Limit Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation. American Psychologist, 66(4), 290-302. DOI link

2. Palmucci, A., & Ferraris, A. (2023). Climate Change Inaction: Cognitive Bias Influencing Managers’ Decision-Making on Environmental Sustainability Choices. Link

3. Supran, G., & Oreskes, N. (2023). Assessing ExxonMobil’s Climate Projections. Science

4. Creutzig, F. et al. (2022). Political Economy of Climate Policy. Link

5. Royce, I. (2022). Political Short-Termism is Putting Our Environmental Security at Risk. RUSI Commentary

6. Paul, M., & Fremstad, A. (2019). Overcoming the Ideology of Climate Inaction. Project Syndicate

7. Dalby, S. (2014). Quoted in Moore, S. (2024). Climate Action in the Age of Great Power Rivalry. Kleinman Center Policy Digest. Link

8. Ripple, W. et al. (2017). World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice. BioScience. Link

9. United Nations (2020). Global Biodiversity Outlook 5. UN Report

10. Heritage Newfoundland (n.d.). Cod Moratorium. Link

11. Our World in Data (2023). CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Link

12. Earth.org (2020). World Fails to Meet Single Aichi Target – UN. Summary

13. Ejsing, M. (2024). Verden er ikke længere den samme – Økologiske krisefortællinger i det antropocæne. Hans Reitzels Forlag.

14. Morton, T. (2013). Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Leave a comment